Beware the Seductive Meta-Narrative! Lazy History and the Flattening of Zionism

By Matt

I.

Two weeks ago, a group of protesters from Sarah Lawrence’s chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) disrupted a primetime campus event featuring prominent New York Times columnist Ezra Klein. Under the pretense that Klein was a “genocide denier,” an “enabler of fascists,” a “normalizer,” and many other unsavory things besides (the word “Nazi” featured prominently on at least one of their signs), the protest leaders shouted disparaging remarks about Klein in front of an audience of hundreds. Despite Klein’s sincere and repeated efforts from the dais to initiate dialogue, they refused to engage with him. Instead, they formed a blockade just beyond the auditorium, where—along with some fifty supporters—they led a series of raucous chants set to the grating clang of a cowbell, making it difficult for audience members to hear Klein’s conversation with SLC president Cristle Collins Judd for the better part of an hour.

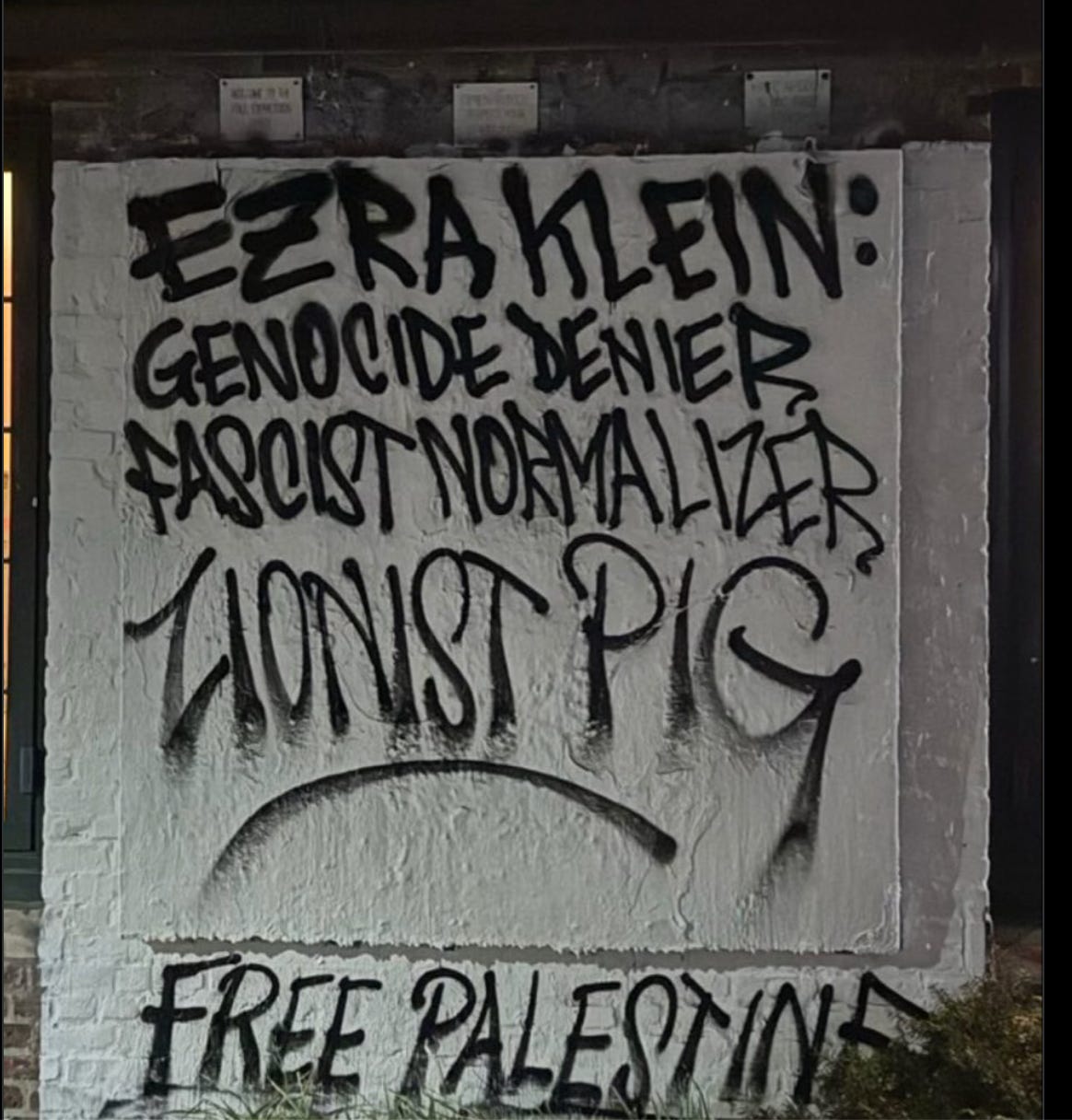

At the center of SJP’s objection to Klein’s presence on campus was their impression that he is a Zionist. Klein’s alleged Zionism—even though he has never self-identified as such and frequently advocates positions that are fiercely critical of Israel—dominated much of SJP’s promotional material before the event. Then came the coup de grace, which many on campus felt crossed a serious line into hate speech: in the lead-up to the event, someone painted the words “Zionist pig,” among a list of epithets directed at Klein, on the College’s “free expression board,” located outside the main dining hall on campus.

Shocking as it was, this was the same playbook that SJP had used to denigrate and delegitimize another invited speaker two years ago: award-winning journalist Jodi Rudoren, then editor-in-chief of The Forward, perhaps the most storied Jewish periodical in the U.S. With the Israel/Hamas war raging and student interest in Palestine/Israel at its zenith, my colleague and I had thought it made sense to ask Rudoren—who had deep experience reporting from Gaza for the New York Times and other publications—to reflect on the challenges of covering the war. But Rudoren’s selection as a keynote was rejected by SJP students well in advance of the event, chiefly because of her presumed identity as a Zionist. The messaging on SLC SJP’s Instagram feed at that time was unmistakable: in one post Rudoren, her likeness surrounded by bloody handprints, was branded “not welcome” because she “is a Zionist.”

What is going on here? I certainly empathize with the anger and frustration of so many of our students, who have lived through Israel’s utter devastation of Gaza over the past two and a half years—war conduct that I agree should be labeled genocidal. I also ardently support our students’ right to protest against the manifold injustices of our moment.

None of that, however, should excuse this appalling spectacle, which felt like perverse performance art—obnoxiously over-the-top, tone-deaf, and needlessly inflammatory, especially considering the irony that Klein shares many of SJP’s positions on Israel and Gaza.

As an academic historian of the modern Middle East, I was particularly struck by the lazy, overly simplistic—indeed, intellectually dishonest—use of the word “Zionist” in SJP’s attacks on Klein. On my campus, at least, “Zionist” has become an expletive, wielded expressly to shut down conversation. It often seems like “Zionist” is the worst thing you can call someone—tantamount to Nazi storm trooper or Ku Klux Klansman. To label your political opponent a Zionist on my campus, as SJP did with Rudoren and now Klein, often seems to imply that you think they are an irredeemable racist—complicit in genocide and aligned with the baby-killers.

II.

The kind of history that has most influence upon the life of the community and the course of events is the history that common people carry around in their heads. It won’t do to say that history has no influence upon the course of events because people refuse to read history books. Whether the general run of people read history books or not, they inevitably picture the past in some fashion or other, and this picture, however little it corresponds to real past, helps to determine their ideas about politics and society.

- Carl Becker, from “What Are Historical Facts?” (1955)

When you’ve read a ton of academic history, as I have, you notice the same kinds of arguments being made over and over. The most typical is about change: why, how, or when it happened, or which of many factors was decisive in catalyzing it. Just as often, however, historians revise older arguments about change by emphasizing surprising or oft-neglected continuity.

Another type of argument I encountered a lot in graduate school emphasizes historical contingency. Where an older generation of historians might have seen some important change as a historical inevitability—due to deep structural forces (or even cultural essences)—revisionist historians instead illuminate the many micro-decisions that actual human beings made to produce a given outcome. To put it crudely, the contingency argument often boils down to saying: “It’s actually a lot more complicated.” This sort of argument can be equally effective at deflating both the right’s essentialist narratives (triumphalist nationalist mythologies, say) and the left’s (e.g., teleological Marxist histories). Contingency-minded historians like to peek under the hood and show us the dead ends, disputes, near misses, and surprising twists and turns that underlie all major change and serious collective decision-making. Change, even or especially progressive change, rarely happens in the neat and tidy way we might think, or wish, it did.

Over the past few years, I’ve noticed the increasing prevalence of a different kind of historical argument. I call it the “stamped from the beginning” meta-narrative, borrowing from the title of Ibram X. Kendi’s National Book Award-winning history of racist thought in the U.S. I invoke Kendi not because I dislike the book or think it’s bad history; Kendi’s analysis raises a raft of important historical questions we need to be grappling with as a nation. Rather, I think Kendi’s title reflects a disturbing habit of mind that has become all too common in what passes for historical discourse in our country these days, both within academia and beyond: namely, the tendency to dismiss massive, complex historical subjects out of hand by branding them with the stigma of original sin.

The “stamped from the beginning” meta-narrative gained popular currency in 2019, with the publication of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s “The 1619 Project” in The New York Times. The project’s historiographical intervention was significant in many respects. Much like Kendi, Hannah-Jones forced us to confront tried-and-true mythologies that have long undergirded our national story. Most centrally, she challenged us to reconsider the temporal bounds of how we tend to narrate that story, arguing that slavery must be front and center in any honest reckoning with America’s founding. This was all commendable.

At the same time, however, “The 1619 Project” played fast and loose with much historical evidence, and it was nearly unanimously criticized on factual grounds by the panel of academic historians who had been invited by the Times to vet it. Perhaps most notoriously, Hannah-Jones doubled down on her argument that the American Revolution was fought in large part to protect the institution of slavery, despite flimsy evidence and the fact that most U.S. historians vigorously disagreed with this interpretation.

Even with all this pushback from the professoriate, the mode of historical understanding implicit in The 1619 Project—slavery and white supremacy as the underlying meta-narrative of American history—is what seemed to stick. Once established, totalizing meta-narratives such as these can take on a life of their own. For instance, when Princeton historian Sean Wilentz intervened in the burgeoning historiographical debate about a so-called “proslavery Constitution” by making a sort of contingency argument—carefully outlining the differences between pro- and anti-slavery forces and rhetoric that prevailed at the time of the Constitution’s drafting—his book was savaged in the New York Review of Books by his former student, Nicholas Guyatt, whose beef with Wilentz seemed to be motivated by an activist conviction that white supremacy, America’s original sin, is the skeleton key that unlocks all of our political history.

The “stamped from the beginning” meta-narrative, which also often takes over in historical discussions of huge topics like capitalism, empire, and liberalism, is understandably seductive. Who doesn’t like to dabble in monocausal explanations now and then? They certainly make the complexity and unknowability of the world infinitely more palatable. The “stamped from the beginning” meta-narrative also mirrors the frenzied media climate of our age—one in which quick or hot “takes” are privileged over deeper understanding and rigorous debate. Many college students, at least at institutions such as mine, face intense pressure not only to have the “right politics” on every issue under the sun, but to perform their political bona fides on campus and in their social media feeds. Having a convenient meta-narrative to do the explanatory heavy lifting for them certainly makes that daunting task much easier.

But it’s not really the students’ fault—not when so many professional historians, who should know better, are leading the way. In my own field of Middle Eastern studies, I see this dynamic most clearly at play with the steady bastardization of Zionism—a complex historical formation that merits the most careful consideration and scrutiny, especially because it is so contentious. But this is not what I feel we’ve been getting—perhaps unsurprisingly, as my field has adopted a much more assertive and activist anti-Zionist orientation.

The “stamped from the beginning” meta-narrative is lazy. Not only does it ignore the complexity of the past—complexity that stems from the immense diversity of the historical actors who seek to shape it—but it also overrides the degree of contingency that professional historians ought to know always plays a significant role in propelling events forward.

It is also dangerous, particularly for the way it tends to neatly divide the world into angels and demons—righteous victims and evil victimizers. If we take such essentialist meta-narratives at face value, then we absolve ourselves from the hard work of exploring the nuances of human behavior, both at the individual and collective level; or of trying to understand the dynamics of a mysterious, foreign past without judging it by the moral standards and cultural frameworks of our tumultuous present.

III.

Studying history calls into question totalizing views of society as governed—and as should be governed—by an absolute coherent voice, and instead does justice to the multiplicity of human voices in society, often contradictory and opposed to each other, and to the complexity of human behavior.

- Alon Confino, from “Miracles and Snow in Palestine and Israel: Tantura, A History of 1948”

Is it possible to advance a suitably critical, comprehensive understanding of Zionism without succumbing to the impulse to flatten all of Zionist history into an overdetermined meta-narrative? No doubt, many on the anti-Zionist left—including many academics within my field—no longer believe this can be done, so deeply ingrained is their conviction that all of Zionism is reducible to a particularly pernicious form of settler colonialism.

I’m going to try, anyway.

The truth is that Zionism is not a monolith. It has always meant, and continues to mean, many different things to different people at different times. The “stamped from the beginning” meta-narrative of Zionism always ignores this fundamental fact.

It ignores the thought of practical Zionists like Lev Pinsker, who argued in his famous manifesto “Auto-Emancipation” (1882) that saving Jewish lives was what mattered most, not a political state and certainly not the ancestral homeland of Eretz Yisrael. It ignores the fact that even Theodore Herzl, the great pre-WWI champion of Zionism who helped organize it into a global movement, was agnostic about the idea of returning to Eretz Yisrael for much of his career (having explored other territorial options, like Uganda, for a period).

It ignores Zionists like Albert Antebi, a Sephardic Jewish leader in Palestine who advocated strongly for learning Ottoman Turkish—then the official language of the land. Or the Zionists who were insistent upon learning Arabic and finding common cause with their Palestinian neighbors.

It ignores cultural Zionists like Ahad Ha-Am (aka Asher Ginzberg), for whom the essence of Zionism was the spiritual awakening of the Jewish people. For him, Palestine was only meant to serve as a spiritual center anchoring Jewish revival, not any sort of majoritarian state where Jews would exercise political sovereignty.

And it ignores pacifist Zionists like German philosopher Martin Buber, whose organization Brit Shalom advocated for a binational state. For Buber and his allies, there was absolutely no contradiction between being a Zionist and believing in the political equality of Jews and Palestinian Arabs.

It ignores the fact that early Zionist “pioneers” in Palestine, in the period now known (however imperfectly) as the “First Aliyah” (c. 1882-1900), were not particularly ideological in their approach to settlement—that they regularly employed Arab workers and were not motivated by demographic domination of the land.

More significantly, it ignores the fact that not every Jew who immigrated to Palestine should be called a “Zionist.” As historian Gur Alroey has demonstrated, many if not most immigrants before 1948 eschewed the ideological bent of the official Zionist movement, choosing to settle in cities where they could continue their daily lives much as before, instead of becoming pioneers in labor-Zionist agricultural projects like the kibbutzim. Alroey argues compellingly that official Zionist history has retroactively sought to claim all Jewish immigrants to Palestine as olim [those who “make Aliyah,” which for Zionists connotes a process of spiritual ascent], even though many of them would never have identified as such. They simply came to Palestine to escape antisemitic persecution, or to have a fresh start outside of Europe, and did not have much interest in ideological nation-building, as it were. Moreover, many of them soon left for greener pastures, finding little in Palestine to like.

In short, there were many ways to be Zionist before the state of Israel’s establishment in 1948, and not all of these implied the pursuit of full political sovereignty, let alone the resort to militancy and violence. And there were even more ways to be Jewish in Palestine before 1948 that didn’t necessarily imply real allegiance to Zionism as a political or ideological movement. It is this underlying diversity of Jewish and Zionist lived experience in Palestine before 1948 that gets erased when we impose a rigid and teleological definition from our polarized present onto a past reality that was far messier and more fluid.

I can already hear the angry retorts. Yes, Palestinian leaders and intellectuals understood the threat that Zionism posed to their own national aspirations and opposed it from quite early on. Yes, the interwar period saw the emergence of the Revisionist Zionists, led by the execrable Ze’ev Jabotinsky, whose notorious “Iron Wall” text (1923) lays out a clear blueprint for military domination over the Palestinians as the only way to secure the goals of Zionism—which for the Revisionists was a territorially maximalist state where Jews were the decisive demographic majority. Revisionism is the ideological core of today’s Likud party. But the Revisionists were never more than a minority within the Zionist movement for a long time, and it is often forgotten that even Jabotinsky explicitly rejected the expulsion of Palestinians as a legitimate option in “The Iron Wall.”

It is true, as historian Anita Shapira tells us, that the Zionist leadership underwent a crucial shift in strategy from the mid-to-late 30s onward, transitioning from a “defensive” to “offensive” ethos in pursuit of the goal of securing a sovereign state. But none of that fully explains the circumstances through which Israel ended up with the state it got, instead of the smaller proposed states that had been allocated for the Zionist movement in 1937 (by the British) or in 1947 (by the UN).

So, then, what about al-nakba? Isn’t Israel’s creation amid a brutal war that culminated in the dispossession and forced exile of 750,000 Palestinians clear evidence of what Zionism had been up to all along?

Not necessarily. As historian Alon Confino has brilliantly argued in his seminal essay, “Miracles and Snow in Palestine and Israel: Tantura, a History of 1948,” the nakba unfolded in real time, according to the logic of war, in a particular post-Holocaust context of Jewish desperation. In his view:

“When it became clear to the Jews during March-April [1948] that conquest and expulsion were working out surprisingly well, with little or no opposition, and at times with Arabs’ own initiatives to leave, they increasingly (though selectively) adopted the practice by April 1948. It was not premeditated but a confluence of particular circumstances in specific time and place: the early voluntary departure of local elite, Jewish victories, collapse of Palestinian society, and long-standing Jewish fantasies on emptying the land. The temptation to clear the land was too strong for Jews once the opportunity presented itself.”

Confino’s interpretation—the most properly historical account of Jewish agency in the nakba that I have encountered—gives us much to chew on. On one hand, Confino doesn’t downplay the role that Jews played in Palestinian dispossession. In clear contrast to official Zionist-Israeli history and so much mythology about the 1948 war, Confino accepts that Jewish forces expelled large numbers of Palestinians and deliberately carried out the erasure of Palestinian society.

On the other hand, Confino refrains from overly simplistic, teleological accounts about Zionist “necessity,” such as the one that Israeli journalist Ari Shavit offered in his morally repugnant 2013 New Yorker article about the Jewish massacre of Palestinians in Lydda in 1948. In that piece, Shavit argued imprecisely and disingenuously that it was all of “Zionism” that “had carried out a massacre in Lydda,” and that this episode was both foreordained and necessary for Jewish survival. “From the very beginning, there was a substantial contradiction between Zionism and Lydda,” Shavit writes. “If Zionism was to exist, Lydda could not exist. If Lydda was to exist, Zionism could not exist. In retrospect, it’s all too clear.” This is simply another iteration of the same teleological meta-narrative that anti-Zionists favor—namely, that ethnic cleansing was inevitable from the beginnings of Zionism. The only difference is that Shavit is okay with it.

But this is total nonsense. As Confino argues convincingly, while it is tempting to assume—especially given the increasing prevalence of “transfer thinking” in some Zionist circles during the 1930s—that something like nakba had always been the underlying goal of the Zionist movement, this view does not hold up under scrutiny. The events that led to the formation of Israel as a Jewish-majority nation-state were in fact sudden and unexpected. As Confino puts it:

“The notion that Zionism right from the start intended exclusively (also before 1939) to create a Jewish nation-state in Palestine is a Zionist teleology that emerged after the foundation of Israel in 1948. The notion that Zionists right from the start intended to expel Arabs is a Palestinian teleology that emerged after their loss of homeland in 1948.”

Moreover, “Zionism” is not a historical actor; it was specific Zionist Jews who carried out the expulsions. They did so, Confino explains, because they were operating within a historical context and moral framework where it made sense to do so—amid a brutal war that was widely understood to be existential for the Jewish people, against the backdrop of a post-WWII world order in which the transfer of massive numbers of displaced persons (DPs) had become the international norm. In Europe alone, there were around 60 million DPs in 1945. And the partition of India in 1947 led to the forced displacement of an estimated 14 to 20 million people.

And what of Zionism since Israel’s founding? It is undeniable that the achievement of a majority Jewish nation-state has narrowed the scope of Zionism in many crucial ways; to identify as a Zionist after 1948 is to accept, on some basic level, that Jews have the right to live in the state of Israel—even if you fundamentally disagree with everything that state has done in the name of protecting Jewish sovereignty (nakba included).

But even after 1948, it is still wrong—still profoundly ahistorical—to assume that Zionism could suddenly be essentialized away as a simple monolith, as if all Zionist Jews and Israelis want the same thing out of Jewish nation-statehood.

To do so would ignore the plight of hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants from Middle Eastern and North African countries (and their descendants), who—as post-colonial scholar Ella Shohat has amply demonstrated throughout her career—also felt themselves to be victims of Zionist ideology and state-building. Many on the left have happily embraced the part of Shohat’s scholarship that highlights European/Ashkenazi racism against the Sephardim and Mizrahim, while downplaying the important corollary to her argument—that Jewish-Israeli society is majority non-white, and that many non-white Israelis have suffered at the hands of white-Ashkenazi hegemony. Seen in this light, we should be chary about equating the history of all Jewish migration to Palestine/Israel with the ideological thrust of white European settler colonialism (which itself, it must be said, is by no means monolithic as a historical phenomenon).

To paint Zionism with an overly broad brush would also ignore all the tensions within Zionism that have bubbled to the surface since the start of Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, following the 1967 War. As contemporary scholarship on religious nationalism has made quite clear, Orthodox Israeli settlers in the West Bank see themselves as the true “Zionist pioneers,” having taken over from an erstwhile generation of secular Israelis who they now see as insufficiently Zionist—too morally bankrupt and hopelessly Westernized to carry the banner of authentic Jewish nationhood.

IV.

The simple fact is that Jewish and Palestinian experiences are historically, indeed organically, connected: to break them asunder is to falsify what is authentic about each. We must think our histories together, however difficult that may be, in order for there to be a common future. And that future must include Arabs and Jews together, free of any exclusionary, denial-based schemes for shutting out one side by the other, either theoretically or politically. That is the real challenge. The rest is much easier.

- Edward Said, from “Bases for Coexistence” (1997)

I do not identify as a Zionist, but I did once; it was simply taken for granted, part of the fabric of my Jewish upbringing. I credit my college years for giving me the time, space, and knowledge to thoroughly explore that identity and ultimately walk away from it. But I wonder how I would have reacted if I were in college now, starting that journey in today’s rhetorical climate—assaulted with epithets by peers who showed no desire to understand me or reach me where I’m at.

The general trajectory of young American Jews like me away from knee-jerk pro-Israel stances has long been the subject of much hand-wringing among major Jewish and Zionist institutions in the U.S. Just last week, the Jewish Federations of North America (JFNA) published the results of a survey that would seem to confirm their worst fears: only a third of American Jews now identify as Zionist, whereas 14% of Jewish young adults now actively identify as “anti-Zionist.” At the same time, however, that same survey indicated that nearly nine out of ten American Jews believe that “Israel has the right to exist as a Jewish, democratic state.”

Where some commentators see confusion or even a latent crypto-Zionism at play in such ostensibly contradictory findings, my wonderful colleague Joel Swanson sees a clear indication that many American Jews now insist upon more nuanced views on Zionism and Israel. What interests me most is the degree to which American Jews are rejecting the basic categories they’ve typically been presented with: that one must be either “pro-Israel” or “pro-Palestinian,” say; or that to be “Jewish and democratic” necessarily implies a Jewish demographic voting majority. As Swanson puts it: “If the survey teaches us anything, it is that this binary of ‘pro-Israel’ versus ‘anti-Israel’ no longer captures how Jews think or speak. The community is wrestling, openly and seriously, with what it means for Israel to be Jewish and democratic, and whether current political realities honor that aspiration.”

It is precisely within this context—as so many young American Jews are interrogating their Jewish identities and rethinking the basic premises of public discourse around Israel and Zionism—that I feel the pre-1948 history of Zionism highlighted in this essay matters so much. This earlier history of Zionist pluralism reveals that Zionism can be dissociated from the political project of building a particularistic ethno-state, and that accepting the idea of a Jewish national home in Palestine need not be equated with the shameful conduct of an Israeli nation-state that has steadily transformed that home into a repressive ethno-nationalist fortress.

The exercise of re-imagining a Zionism untethered from the present reality of Israeli nation-statehood is not merely academic. Instead, it allows us to envision the “common future” for Palestine/Israel that Edward Said argued for in his powerful essay, “Bases for Coexistence”—a future where the land must be shared among two national communities with equal rights, whatever the political configuration that ultimately supports that. When Said argues that Israeli Jews and Palestinians “must think [their] histories together,” he is emphasizing the historical reality that Jewish and Palestinian lives are inextricably intertwined, and always will be. But I wonder if he wasn’t also tacitly acknowledging the idea that the end of Israel as we know it today won’t necessarily spell the end of Zionism; and that perhaps some of the older alternatives contained within Zionist history could be the starting point for a blueprint of what a future pluralistic society in Palestine/Israel could look like. After all, it is absurd to think that Zionists won’t be involved in mapping out a shared future in the Holy Land, just as Afrikaners were always going to play a major role in transitioning South Africa away from apartheid.

Let’s hope this moment of reckoning comes sooner rather than later, because the state of Israel’s conduct towards Palestinians has been indefensible and is only getting worse. There is no excuse for the genocide in Gaza; for Israel’s mass imprisonment of Palestinians and use of torture; for its illegal occupation of Palestinian territory and its enablement of fanatical settler pogroms against Palestinian villages; for the disproportionate collective punishment inflicted during the Intifadas; for massacres of Palestinians committed during the nakba and after.

Zionism’s main problem today, in short, is the state of Israel. Not the founding Zionist visions that set the nation-building process in motion, but the country it has actually become since 1948—a country that started with the deliberate dispossession and erasure of Palestinians from the landscape; continued after 1967 with a brutal and unjust military occupation that deprives Palestinians of their most basic rights; and has culminated in the current government’s brazen attempts to annihilate the Palestinian presence from Gaza and the West Bank. If Zionism means defending that Israel at all costs, then of course many American Jews are going to abandon it, as I did over two decades ago.

But all of that doesn’t mean the only path towards Palestinian liberation is the complete rejection of Zionism’s foundational claim that Jews have a right to some kind of national life in Palestine. One need not fully accept Israeli novelist Amos Oz’s sanctimonious claim—“The Zionist enterprise has no other objective justification than the right of a drowning man to grasp the only plank that can save him”—to acknowledge that Jews in 1933, 1939, and especially 1945 needed a place to go, when the world’s doors were almost categorically shut on them.

Regrettably, the “stamped from the beginning” meta-narrative that prevails in many anti-Zionist circles right now completely erases this important dimension of pre-1948 Zionism as a Jewish liberation movement. Instead, it shoehorns the complexity and diversity of Zionist history into a reductive framework that assigns uniformly malevolent intent to a people who, in their time, were also just trying to live. This mode of historical understanding ultimately dehumanizes millions of Jews and Israelis: by branding them with the original sin of genocidal settler colonialism, they are deprived of their agency and complexity as human beings making difficult decisions in impossible times, and are instead transformed into a faceless and evil political abstraction. Once dehumanized in this way, it is not a far leap to what historian Yoav Di-Capua has called “genocidal mirroring,” a political outlook that clamors for an ethnic cleansing of Jews from Palestine.

In a recent edition of KITE, a weekly newsletter published by Sarah Lawrence’s chapter of Faculty and Staff for Justice and Palestine (FSJP), one of my colleagues defended the labeling of Ezra Klein as a “Zionist pig” by defining a Zionist as “someone…who supports the state of Israel as it commits a genocide.” Though this formulation might seem simple enough, it is deeply unfair and disingenuous—a way to silence political opponents and stifle much-needed discussion and debate. Moreover, I contend that this definition would actually exclude most Zionists, who support Jewish national life in Israel but are staunchly opposed to the genocide in Gaza. We need to be better than this, in our campus classrooms and public discourse about Palestine/Israel. We must insist on decoupling Zionism from full-throated support for Israeli atrocities. And we must extend our empathy to those who hold positions somewhere in the muddy middle between our polarized extremes—those who, like Edward Said once did, yearn for a future where Palestinian liberation and Jewish national life in the Holy Land aren’t mutually exclusive.